STILL SENT:

MOTEN AND HARNEY

READING GROUP PORTFOLIO

SCHEDULE

PART I: AESTHETIC SOCIALITY OF BLACKNESS

I. BLACKNESS

Undocuments | Snuggling Up

II. SOCIALITY

Motley Crew | Snuggling Up, Again | Village Narration | Counterclaim

III. AESTHETIC

Bodies in Motion | Sonic Confusion | Traitorous Smell

SCHEDULE

Week 1: Andaiye and Asset Class

Andaiye and Alissa Trotz (editor), The Point is to Change the World: Select Writings of Andaiye:

Forewards

Chapter 2

Part II

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Harney and Moten, “On the status of a new asset class.” Busan Biennale (2024).

Martin, Randy. "After economy? Social logics of the derivative." Social Text 31, no. 1 (2013): 83-106.

Moten, “On Criticism: Studying How We Are Together.” Portable Gray 7.2 (2024).

Week 2: Experiments in Exile

Laura Harris, Experiments in Exile: C. L. R. James, Hélio Oiticica and the Aesthetic Sociality of Blackness (2019)

Background:

Fred Moten, Stolen Life (2018):

“Knowledge of Freedom”

“Gestural Critique of Judgement”

“The Touring Machine (Flesh Thought Inside Out)”

Week 3: Billie’s Bent Elbow

Fumi Okiji, Billie’s Bent Elbow: Exorbitance, Intimacy, and a Nonsensuous Standard (2025)

“Blue(s) as Cymbal: Beauford Delaney (Elvin Jones) James Baldwin.” Speculative Light: The Arts of Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin (2025).

Background:

Fred Moten, Black and Blur (2017):

“Taste Dissonance Flavor Escape (Preface to a Solo by Miles Davis)”

“Sonata. Quasi Una Fantasia”

“The Phonographic mise-en-scène”

PART I: AESTHETIC SOCIALITY OF BLACKNESS

Learie Constantine walks out onto the cricket field in about 1932.

Installation view of Hélio Oiticica, Eden, at the Carnegie Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

Laura Harris offers us a vital framework for this reading group: the aesthetic sociality of blackness. Throughout her book, this concept returns without a full definition, but instead, a series of assembling enactments that contour its form and flow. Harris writes: “the aesthetic sociality of blackness is extended in these contact zones, through the conflicts erotics, and generativity of interclass and interracial and queer collaboration and the disruption and reconfiguration of gender structures that occur within the new notions of production and reproduction that this collaboration requires” (7). The aesthetic sociality of blackness points to the “ongoing recollective but also innovative and experimental insurgent expression” of blackness--an unfixed, expansive formation not bound to identity but to an alterity of movement and gathering.

“The aesthetic sociality of blackness is an improvisational assemblage that resides in the heart of the polity while operating under its ground and on its edge. It develops by way of exclusion, but it is not exclusionary. And it extends itself through forms of association, affiliation, kinship, and reproduction that do not confine themselves to any norm. Though it draws on and carries forward what James Baldwin describes as an “unwritten, dispersed and violated inheritance,” it is not a re-membering of something that was broken but an ever-expanding invention.”

(Harris, 33)

In what follows, we will break apart each of the terms--blackness, sociality, and aesthetics--to parse what Harris is theorizing, but more critically, we will use Harris’s provocations to think across major texts of this reading group. In a way, we want to consider the aesthetic sociality of blackness found in these clearly connected but distinct and divergent works. What is possible when these works are made to collaborate, to allow their erotics to reshape each other? To seek the “ubiquitous modes of contact that are often overlooked in or dismissed by prevailing forms of regulation” (33). Again, borrowing from Harris on her own making-intimate of C.L.R. James and Hélio Oiticica:

““The differences at issue here are not those that separate them but those that structure and animate the sociality they each engage, enter into, and valorize in resistance to the mythologization and violent reinforcement of ‘the given’” (30).”

The aesthetic sociality of blackness is a mode of relation, gathering, intellectuality, and innovation. We must think generously with it, but it is not passive, it is not a well to freely take from, but an actant upon the world through those that live, work, and create in it. So as we make “claims on the aesthetic sociality of blackness, it made its claims on [us], erupting in and through [our] work, appropriating [our] media and [our] authorship as its means of expression.” So what are we making? What are we giving? How are we to be used?

We begin with the last term of Harris’s phrase—the term that shapes the possibilities of the terms that precedes it: blackness. Harris is quick to make clear that blackness here does not “mean to indicate, or to only indicate, African descent” (2). Instead, she follows many in black studies that “have theorized blackness as that which designates irreducible difference, a mode of being that the modern bourgeois subject, conceived in and by European thought— the sovereign subject who is the model for both citizenship and aesthetic authorship— cannot accommodate” (2-3). She continues throughout the rest of Experiments in Exile:

II. BLACKNESS

“Blackness, in this sense, manifests itself in what is perceived as the unruly creativity and disorderly sociality that the subject, in its commitment to the idea of its own freedom as self- determination, as the self- conscious exercise of pure individual will, secured by self- possession, must at all costs defend itself against, however violent its defensive maneuvers may be as it confronts the impossibility of this ‘freedom.’” (3)

“Blackness, in the sense that I invoke it, as an always already given impurity, is an expansive formation whose boundaries and associations are not fixed. The aesthetic sociality of blackness is its ongoing recollective but also innovative and experimental insurgent expression.” (4)

“What also emerges in these descriptions is something like a definition of blackness as fundamentally heterogeneous or motley, one in which mixture itself is incomplete and difference is neither subsumed nor sublated but preserved within and as a history that depends on conjecture.” ”

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé P15, Capa 11, Incorporo a Revolta, 1967. Photographs by Cláudio Oiticica

George Headley, a Jamaican cricketer who played for the West Indies. One of the greats and a major player for James’s work on cricket.

Blackness then becomes not a “[vessel] or [vehicle] for the projection of the subject but alternative contact zones where new relations or, rather, new experiences of enmeshment could be worked out” (7). For Harris, this gives space to study C.L.R. James’s work on cricket, Helio Oiticica’s work on samba, their individual exiles to the US, and the possibility of reading these two artists together despite the profound distinctions in identity, work, class, politics, and time.

Undocuments

For both James and Oiticica, the aesthetic sociality of blackness is something they arrive in and then choose to be reshaped by. Blackness becomes a propulsion and guide for their individual journeys with collectivist and antagonistic political and artistic work that prioritized “experiments in the practice of assembly” (8). In rejection of the individuation of the artist, their work sees the proliferation of the “undocument,” where “the work”—the complete object—is unworked, is made all incomplete by the endless,

“efforts to socialize authorship and the intellectual function to dealienate work from the work while acknowledging that the socialization of the intellectual function requires the materialization of the work in some form as a meeting point, a nexus for contact.”

Samba as bodily, erotic, relation--sociality: Cardoso, Ivan, HO (1979): experimental documentary on Hélio Oiticica and his works, specifically, Parangolé.

Lance Gibbs’s javelin, spinning bowl

As Oiticica wrote in a letter to Allen Ginsberg:

“this publication will function as a gathering of projects for experimental activities and propositions and also as a record of some experiments anonymously carried out and general ideas based/developed on the outcome/crisis/possible consequences of extreme problems which present themselves as opened rather than tending to a solution.” (138)

As Harris summarizes of the two artists and the undocuments:

“James and Oiticica sought to create the conditions of possibility for new modes of sociality in and through a socialization of the intellectual function, a dialectical process that must materialize in and as a work even as it would immediately seek the unworking of that work by way of a counterclaim that James and Oiticica now actively courted (or cruised).” (159)

What we see in these proliferating undocuments of unwork is how blackness, when entered and when allowed entry into us, becomes a “dispersal and unraveling” of identities, and for Jams and Oiticica, this “diffusion of their works and the grand narratives and ideals that those works were supposed to embody that James and Oiticica become black intellectuals” (58-9).

Snuggling Up

Atlantics’ Mati Diop on Her Cinematic Inheritance, TIFF Originals, 2019.

Mati Diop, as referenced by Okiji, on the role of the fantastique and African Cinema: Mati Diop, Atlantics post-screening Q&A, TIFF Originals, 2019.

Thinking with this conception of blackness, we can turn to Fumi Okiji theorizing of “nonidentity or contradiction, a structure of mind that impedes a ‘tarrying with the negative’” (53). Okiji is thinking through the negatating prefix (the un-, non-, and dis-) that unmake sensuous—that is, tactile, identificatory—relationality. She writes:

“The idea is that groups that are “stuck in racial thinking” (of which, incidentally, the entire field of black studies might most obviously be accused) are insular and unable to commit to projects of radical openness that speculative thought and its unfolding toward freedom call for.”

Cecil Taylor, Unit Structures, liner notes, 1966.

Okiji is holding a profound and animating contradiction: of desiring to come together without demanding to find “oneself in the other;” that is, “a comfort with or openness to the exorbitance/underdetermination that the coming together of incompatible approaches / internal laws results in.” To seek an event that “give[s] occasion for the cultivation of a mimeticism of nonsensuous correspondence, a coming/being together beyond resemblance (and distinction).” (47-8).

In contrast to European thought’s fondness for clarity whereby contradiction must be organized into discrete determinations (including the “shock-jock” rhetoric of Zizek and Hegel, their tabloid-like debates around culture clash, which, for Okiji, reveal a desire for universalism and certainty, despite theoretical concepts that seem to attest otherwise), a mode of correspondence where we might “snuggle up” to difference refers to a situation where “we might leave each other free but not alone” (65). That is, an embrace of non-relation “that is not received as laceration of self isn’t really received at all. The non-given mustn’t be missed, it can’t not be concerning, it can’t be understood (which must be understood [in Western culture]), and it can’t be left entirely alone [either]” (59).

What also emerges in these descriptions is an understanding of blackness as fundamentally heterogeneous or motley, one in which mixture itself is incomplete and difference is neither subsumed nor sublated but preserved within and as a history that depends on conjecture. Following Okiji, we may say blackness is the operation of a “conceptual abundance[, and] provide[s] an opportunity for creative reconstruction, even as the threat of interpretative proliferation encouraged by such heterogeneity intensifies its blur” (65-6). Or as Harris writes, “Blackness binds them, creates a collective through them, but without resolving any of the tensions that arise within the context of this collective” (50).

Alissa Trotz, David Austin, and Firoze Manji on “The Absence of Care is Death”: The Point is to Change the World: A Conversation, Daraja Press, October 14, 2021. (54:46-1:03:20)

II. Sociality

Motley Crew

Andaiye on Walter Rodney, James, and “self-activity of the working people”: Horace Campbell and Andaiye on Walter Rodney, Red Thread Women’s Centre Guyana, August 24, 2023. (34:43 - 38:08)

In this understanding of blackness, we can begin seeing the inherent sociality at play—the modes of relation, intimacy, and desire. That is, these alternative modes of kinship. For Harris, this is most acutely demonstrated and performed by the motley crew.

“In The Many- Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, the historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker uncover the lost history of the motley crew, an insurgent social formation that emerged from the connections that developed between the disparate people, violently dispossessed and dispersed by the interlinked systems of enclosure, whom settler colonialism and slavery forced into brutal regimes of labor, who composed what they call the Atlantic proletariat of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries.”

Hélio Oiticica, Tropicália, Penetrables PN 2 ‘Purity is a myth’ and PN 3 ‘Imagetical’ (1966-67)

The motley crew is thus a sociality that “emerged in and through internal and external dissonance and dissidence,” that it is not unified via constrictive categorizations of identity (re: nonidentity). Its “coherence” instead comes from a “fundamentally ‘cooperative and laboring’” formation, a “creative” and “wayward reproductivity”—“multitudinous, numerous, growing…a feminized chthonic monster” (17).

This is the “Mother-Cell” for Oiticica:

“The idea of the Nests began there [London] and with them I arrived as if it were the limit of everything: the need to develop more and more something that would be extra- exhibition, extra- work, more than a participating object, a context for behavior, for life; the Nests propose an idea of multiplication, reproduction, communal growth.” (101)

And what Correspondence/Correspondence was for James:

“to make possible not only new forms of organization but a deconstruction of the body politic, by way of correspondence in every possible sense, through a generative, intramural communication between the dispersed insurgent elements that constituted the remains of the motley crew.” (89)

“Openness to difference was fundamental to the project, and that demanded experimentation; only through experimentation, through trial and error, would they be able arrive at the kind of organizational form they desired but were not yet able to produce.” (93)

While Linebaugh and Rediker see the motley crew as a past event that falls apart in processes of racialization, Harris argues—through the work of James and Oiticica—this “motleyness reemerges as action in concert: in unharmonious revolt and in the revolutionizing of harmony” (18) in the continuing, adaptive aesthetic sociality of blackness. As Harris writes, “It is a mode of intellectuality that, in the face of the vicious constriction of life, assumes the widest possible range of expression— sensual, erotic, sometimes even violent. In pursuit of its own forms of pleasure or “happiness,” it defies the laws of property and propriety” (33).

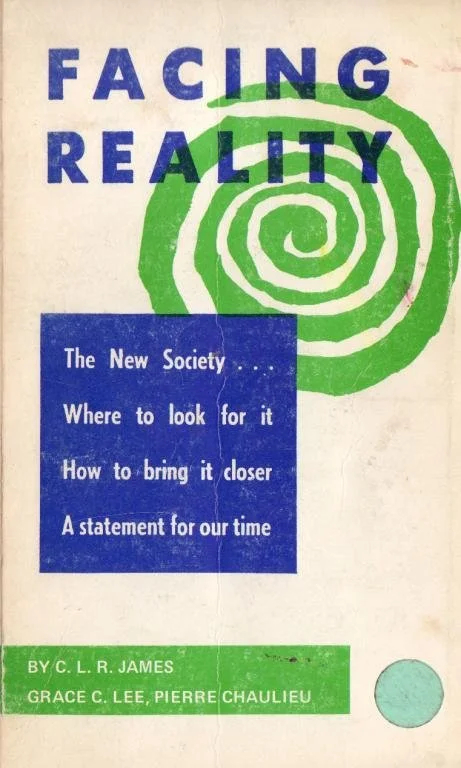

Considered Correspondence’s most important contribution. A critical, Marxist history of the Hungarian Revolution published in 1958 that questions the role of the vanguard, imagining other modes of collectivist experience.

For more on Facing Reality, see: Goldner, Loren. “Facing Reality 45 Years Later.” December 16, 2005. libcom.com.

Snuggling Up, Again

Mary Lou Williams and Cecil Taylor, Ayizan contrasting pianos

Oriki de Exú / Passo a passo - Èṣù ọ̀ta òrìṣà a reading of the poem and a breakdown of pronunciation

It is helpful to return once more to Okiji’s “snuggling up.” Take as an example, her turning to Cecil Taylor and Mary Lou Williams’ contrasting duo-piano concert (documented on the album Embraced with separate/individuated piano tracks), which to Western normativizing ears is a failure—a clashing, disorienting, disclarity. Cribbing from Okiji’s description of Cecil Taylor, we can think of the motleyness of blackness’s sociality as a “poetics—a synesthetic, anamnestic, polyglottic tongue—[that] demonstrate[s] how we might be together when we are not a given for one another, how we might nurture nonidentity in inseparability” (Okiji, 47), a mode of correspondence where we might “snuggle up” to difference, where “we might leave each other free but not alone” (65). A sociality of and in and through difference.

This snuggling up also points to the sociality of “twoness” that Okiji sees in the African subject:

“The Ibo philosopher Chris O. Ijiomah tells us that the “African world- view. . . accepts the coexistence of seemingly opposing realities which however complement each other. This is what is expressed in the proverb, ‘wherever something stands, something also will stand beside it.” From this point of view, “two contrary realities can unite without producing a contradiction. ”

These contradictory qualities or positions, for blackness, can hold together without the need to push through to greater determination and without the profound anxiety that accompanies the contradiction in Western thought. Okiji uses as an example “this verse of oríkì in praise of Èṣù, the Yorùbá òrìshà who presides over the principle of contradiction, twoness (what Moten might call the“blur”), and indeterminacy:

“The short and tall one Whose head is barely visible when [they] walk through a peanut farm Thanks to the fact that [they are] very tall But Èsù must climb the hearthstone in order to put salt in the soup pot.”

Okiji considers [the African] capacity to satisfy the interests of both worlds the defining significance for black thought.

“This figure [the black thinker] registers the constraints—or the impossibilities—that mark its ‘position of noncommunicability’ even as it appears to leap across the abyss. The black scholar writes as though they had the capacity for relation; they chart a path of thought as if this could be legible to the world and as though their formulation might come to hold some authority.”

Sociality is thus a fabulation—a practice of envisioning and dreaming “across the abyss.” But this is also more than imagining, it “alludes to an inherited structure of thought, our common ‘sense of being” (44). In Okiji, blackness’s sociality is a creative practice of gathering together in difference across, borrowing from José Esteban Muñoz, the then and here, the now and there.

Village Narration

George Lamming on Colonial Reshaping: Lamming on In the Castle of My Skin, NCF Barbados, June 5, 2014. (1:18 - 2:44)

At tension in Harris’s and Okiji’s studies is the role of the individual artist and their relationship to blackness—as Harris defines it. How do we hold the artist or theorist without mythologizing and creating a gravitational well of the auteur genius?

In her engagement with the speeches and novels of George Lamming, Andaiye examines how Lamming, in In the Castle of My Skin, disrupts the narrational voice of the novel by centering not the individual hero but the village: a collective narration and protagonist. The problem, she writes, of the “hero” is that:

“The function of the hero/heroine in most novels is to make an experience and change through it. Succeed or fail, there is an individual transformation, a new self-consciousness; the heroine or hero finally understands what is going on in her/his life and/or her/his society. The situation and characters may move on and change, but none besides the main character transforms themselves or us. It is fundamentally an elitist framework.”

Instead, Lamming’s village point of view that invites the reader:

“to appreciate the contribution to laying out the truth of every unique individual usually hidden behind the “ordinary” non-hero or heroine. Then the progress of each is dependent on the collective wisdom and progress of all. G is all the things that Ma and Pa and his long-suffering mother and his experience of Empire Day have taught all of them, all the boys trying to figure out what it is they are living through. It is a collective enterprise and learning and revelation.”

What Andaiye shows us is that the collective holds individuals, but individuals who are perpetually connected and purposefully dependent on each other. “Change is individual but it is also collective,” she writes. “The whole community makes its points of reference, which in turn incite other individuals who give direction to the making of history” (24).

Counterclaim

George Lamming on Colonial Reshaping: Lamming on In the Castle of My Skin, NCF Barbados, June 5, 2014. (1:18 - 2:44)

As Harris shows us in the flow between the individuality of James and Oiticica and the bodily enactments of collectivity in cricket and samba, blackness’s sociality arrives in “a very different kind of work in which collectivity is not preestablished but develops out of cooperation, through what James calls ‘spontaneous self-discipline and cohesion’ and what Oiticica terms ‘anonymous collective genius’” (Harris, 33). Where “Authorship emerges … as a complex relation between discovery and invention, finding and experimentation, taking and releasing” (43). That is, the collective makes use of the individual. What Harris names as the “counterclaim” of blackness.

Writing of James and Oiticica, Harris argues that “the aesthetic sociality of blackness resists any easy appropriation. If James and Oiticica made a claim on it, it also made a claim on them, undertaking its own experiments in and through James’s and Oiticica’s aesthetic work, reconfiguring and rerouting both of their projects in ways they had not anticipated” (5).

This “counterclaim” is most apparent, Harris argues, when blackness “disrupts” that which uses it:

“The counterclaim that the aesthetic sociality of blackness makes on James’s and Oiticica’s works manifests itself more fundamentally when the sociality they invoke disrupts the form of James’s writing and Oiticica’s art in ways they cannot fully anticipate or control— in ways that ultimately call into question the very idea of the work as they had previously understood or attempted to reimagine it.”

We need to think of these reciprocal claims as forms of sociality, a flow between forms, bodies, histories, and desires—a kind of erotics coming from and in service of blackness. Or said more succinctly: the sociality of blackness is aesthetic.

III. Aesthetic

Bodies in Motion

C.L.R. James, Relation, Cricket-in-Action: Burton, Humphrey, Beyond a Boundary (1976), BBC. (20:42 - 28:02)

George Headley bowling

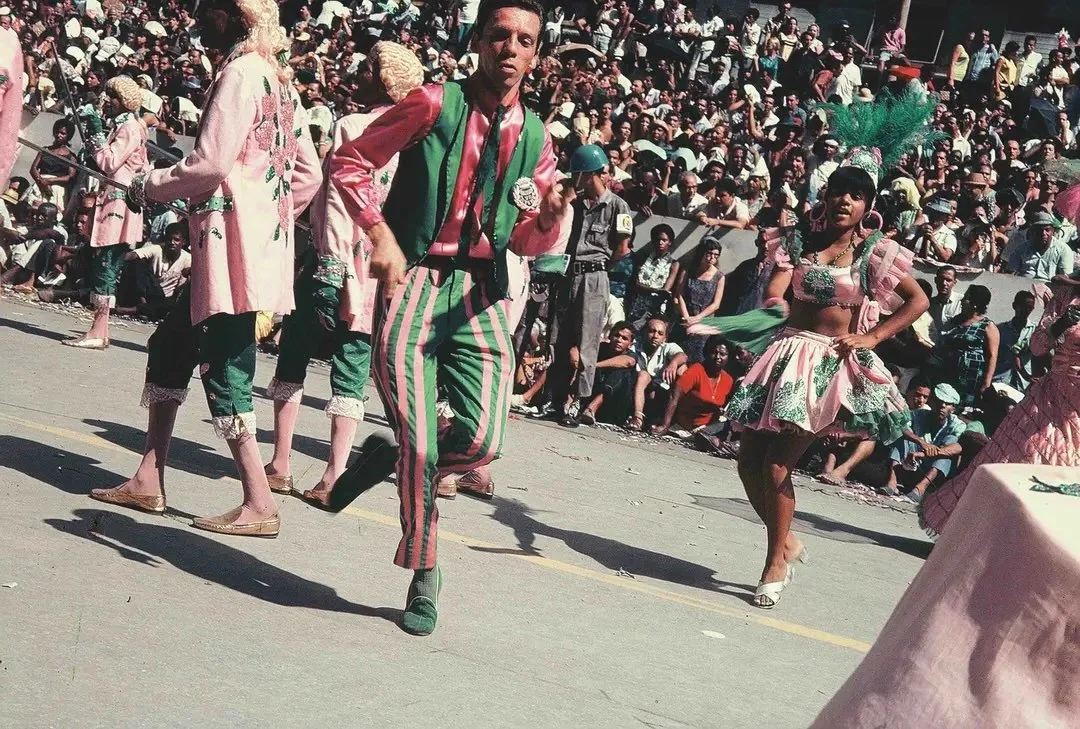

To begin addressing what makes blackness’s sociality aesthetic, we return to Oiticica and the specific and unique movements of samba:

“The passistas . . . seem to be inspired by the meandering space of the favela-labyrinth, as if they reproduced the movements of the body upon ascending the steep roads of the favela. The dance of samba would be in a mimetic relationship with the rhythm of the changes. […] Danced samba would be, therefore, a representation of the route of the favelas, the special labyrinthine expression that infects the movements of the body.”

Hélio Oiticica parading with the Samba School Estação Primeira de Mangueira, Rio de Janeiro, circa 1965-1966.

Through bodily performance, the samba becomes an aestheticization of the life of the favela—not of individual lives but of the “generalized practice” of favela, the quotidian facts of a space and time (39). In this way, “samba generates images…a ‘new discovery of the image,’ and, by extension, ‘a recreation of the image’” (37).

An unfixable, uncapturable image, the aesthetics of blackness’s sociality are “the style that is common to the manifold motions of the great players,” the “perfect flow of motion,” as James writes (qtd. in Harris, 37). That is, it is aesthetic in that blackness is bodies improvising in and through marginality, a collective enacting and reenacting “self-conscious acts in pursuit of pleasure and happiness” (43).

Sonic Confusion

Slavoj Zizek - Haiti Revolution and Napoleon

In the opening chapter to Billie’s Bent Elbow, Okiji interrogates Slavoj Žižek’s (mis)reading of the Haitian Revolution where he tells us “outright that the Haitians were mistaken to believe that the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man—the French Republic’s very first article, on the inalienable right to freedom—was written with them in mind. They ‘miss the point’” (21). For Žižek, argues Okiji, the enslaved’s “mistake” retroactively “repairs” the universality of France’s declaration.

However, beyond the desperation to recoup a Eurocentric ontology, Žižek “moves on too quickly” from the “sonic confusion” that occurred amidst the Haitian Revolution: Haitians soldiers, in revolutionary struggle, singing La Marseillaise. As Okiji writes:

“Žižek does not register this polyglot chorus… He does not appreciate that the African and Creole accents’ disfigurement of the French language provides a metaphor for the dialectical movement of the unfolding of freedom in this age of revolution. … Europe’s anthem is disarticulated by Africa’s sound, practically unrecognizable.”

The sound of Haitian speech—the sonic aesthetic of creole, an opaque transfiguration of French away from the French—does not “repair” European universality, it reconstitutes its. It is “transfigured by literal enslavement and race, by a place at the margins, by illegitimate participants” (25). Haitian creole rewrites the standard of universality. In the aesthetic sociality of blackness, “Haiti becomes not a subsidiary, a mere dialect of the world historical, but, for a time, the paragon, in relation to which Europe becomes a mere precursory accent” (26).

Traitorous Smell

In his late 1982 speech, “A Visit to Carriacou,” George Lamming spoke of class consciousness, saying no one is born a Marxist; we learn it, we live it. “When a man tells me he is a Marxist,” said Lamming, “… I want to know how he got there.” Class consciousness is a journey, and the ability to tell that story, to recount your connection to and struggle towards a working-class political life—what we may be able to see as a part of the aesthetic sociality of blackness—tells others the truth of commitment, of care for the work. When Lamming says, “I lived with class … I did not discover how class society deforms human relations from Marx. I lived it. And so I developed an extraordinary nose. I can smell middle class people everywhere,” he is telling us that there is an aesthetic to the middle class—an aesthetic that

does not smell right, does not harmonize and flow with the material realities and threats of life in Grenada, the Caribbean, the world. (qtd. in Andaiye, 29).

We turn to this speech of Lamming’s and Andaiye’s reading of it, because we must also take up how the aesthetic sociality of blackness trains the body to see, hear, and smell aesthetics of the ambivalent, the compromised, the traitorous, and the infiltrative. As opposed to a paranoid position, what we are speaking of is how blackness is set upon by criminalization, but more crucially, how, as Andaiye writes, “those we nurture and sacrifice into power help not us, but our enemies” (25). Andaiye and Lamming are confronting the material history of how children were sent away into education to “rescue [their] offspring from the humiliations [their] ancestors endured” (qtd. in Andaiye, 28). How being sent does not promise an advancement for the village or an escape from humiliation, but merely a different kind of humiliation, a forgetting, “a complete wiping’ out” of memory, “leavin’ only what they learn”—an emptying out of the self to enter “a derivative middle-class” (34).

Andaiye and Lamming are not demanding an abandonment of those that have been sent, or those that return, but a recognition of the “betrayal of class” that is the secret foundation of the institutions we enter. Andaiye reminds us that this is not a “purely personal act,” but one that comes with being emptied. She helps us understand that the aesthetic sociality of blackness can be an aesthetic that helps us resist, that can keep us full, that “keeps the camp clean” (23) so we and it can keep up the work, keep up the care, keep up the sociality.