Archival Practices and Lineages to Come

Black Visual Intonation: History and Possibilities | GSU Students Work on Black Visual Intonation | Arthur Jafa’s Archival Impulse | Kahlil Joseph’s Belhaven Meridian | Black Intentionality | Jenn Nkiru’s Cosmic Archeology II | Motion Practice | The Unruly Archives of Hip Hop Music Videos

Black America Again, Bradford Young with Common, 2017

Black Visual Intonation - History and Possibilities

Introduction:

One of the “lineages to come” Larry Clark ushered in with his film Passing Through (1977), centers on filmmaker and visual artist Arthur Jafa, who, by his repeated admission, is “obsessed” with Clark’s film.[1] This is because for Jafa black music still remains the art form where black people are the most “actualized” and the film contributed to the beginning of his quest for what he calls “Black Visual Intonation:” the study of how black image-making might aspire to “the power, beauty and alienation of black music.”[2] Or, even more specifically, as he has said, “How can we analyze the tone, not the sequence of notes that Coltrane hit, but the tone itself, and synchronize Black visual movement with that?”

Jafa began formulating, and experimenting with, his concept of “Black Visual Intonation” while working with Julie Dash on Daughters of the Dust (1991), which became a major source of inspiration for Beyonce’s Lemonade, co-directed by Kahlil Joseph. Jafa and Dash had two primary preoccupations: rendering of black skin on film (sensitometry); and Jafa’s own idea of using non-metronomic movement to create new spaces of possibilities for the movement of black bodies on film. They were also experimenting with the possibilities and limitations of processes of “identification” on the part of the audience, an idea that Jafa later described as a problem of “empathy,” which he has described as a “muscle” that white people – and dominant culture, more broadly- has not developed as much as minority subjects, who have no choice but to learn to “identify” with others in the media.

The essay that eventually took the title of his most popular concept, i.e., “Black Visual Intonation” was a paper originally presented at the Black Popular Culture conference co-organized by Michele Wallace and Gina Dent. It was originally titled “69” and has been reprinted in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, edited by Robert G. O’Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998): 264-268.

[1] Larry Clark and Haile Gerima (Bush Mama, Sankofa) were at UCLA at the same time. When Gerima graduated and began teaching at Howard University he acquired a copy of Passing Through. There he has been teaching the film since. The first reel of the original print was soon worn out supposedly by two students who had watched it over and over again: Ernest Dickerson, who shot Do the Right Thing, School Daze, Malcolm X, The Wire and a number of music videos, and Arthur Jafa. See liquid blackness in conversation with Larry Clark (interviewed by Alessandra Raengo, Spring 2014)

[2] This is also the “mantra” that TNEG, the production company he founded with Malik Sayeed and was joined by Elissa Blount Moorhead in 2013 has adopted are their mission statement.

In Conversation with musician Steve Coleman, Jafa explains what he means by Black Visual Intonation

Source:

“Love is the Message: An Evening with Arthur Jafa.” Youtube, uploaded by Hirshorn, March 16, 2018.

Source:

“Arthur Jafa and Helen Molesworth in Conversation.” Youtube, uploaded by MOCA, April 11, 2017.

Arthur Jafa and MOCA curator Helen Molesworth explore the system of white supremacy that transpires from Love is the Message, the Message is Death, processes of split identification and alienation for audiences of color who are watching mainstream media.

Sources:

Arthur Jafa, “Black Visual Intonation,” in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, edited by Robert G. O’Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998): 264-268.

Arthur Jafa, “My Black Death” In Everything but the burden: what white people are taking from Black culture, edited by Greg Tate (New York: Broadway Books, 2003): 245-257.

Arthur Jafa, My black death. Moor's Head Press, 2016.

Aria Dean, “Film: Worry the Image,” Art in America (May 26, 2017)

Christina Knight, "Feeling and Falling in Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death." The Black Scholar 49, no. 3 (2019): 36-47.

Calvin Thomkins, “Arthur Jafa’s Radical Alienation,” The New Yorker, December 21, 2020

Acting as cinematographer, Arthur Jafa experiments with non-metronomic movement in July Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Four Women (Julie Dash, 1975)

While studying at UCLA, Julie Dash had already made a short film that was extraordinarily sensitive to movement. Set to Nina Simone’s ballad “Four Women,” dancer Martina Young interprets all of them: “Aunt Sarah,” “Saffronia,” “Sweet Thing,” and “Peaches.” Camera angles, use of slow motion and stillness, and expert editing on the gestures that identify and distinguish these character indicates a previous research on the possibilities of disarticulating the black moving (and dancing) body from the demands to “feed” the cinematic apparatus in pre-determined and containable ways.

Watch:

Daughters of the Dust (Julie Dash, 1991)

Within the vast literature on Daughters of the Dust, here we only highlight Diana Pozo’s reading of the liquidity of color, which she calls “water color,” and approaches as a radical aesthetic practice. We understand it in the context of seminal works on “sensitometry” as well as John Akomfrah’s concept of “digitopia,” for the way it homes in on the research on sensitometry that had preoccupied African Diasporic cinema and fueled a “digitopic yearning,” i.e., the conviction that digital technologies could reconfigure the poetics of black filmmaking.

Black Visual Intonation is only the most popular of Jafa’s foundational concepts regarding a black filmmaking aesthetics, which we already explored in the section Arthur Jafa’s Theories of Black Filmmaking and Black Art in Motion . As such, it should be understood within that broader context.

Please also consult additional resources on Jafa and on the liquid blackness research project on his 2013 experimental documentary Dreams are Colder than Death

We also believe that Black Visual Intonation is really a question about what black filmmaking practice and praxis might be able to achieve as it intervenes in the architectures of black filmmaking and black art.

Sources:

Roth, Lorna. "Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity." Canadian Journal of Communication 34, no. 1 (2009).

Akomfrah, John. "Digitopia and the spectres of diaspora." Journal of Media Practice 11, no. 1 (2010).

Pozo, Diana. “Water Color: Radical Color Aesthetics in Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 11, no. 4 (2013): 424-437.

Yue, Genevieve. "The China Girl on the Margins of Film." October (2015): 96-116.

Keeling, Kara. "3 Black Cinema and Questions Concerning Film/Media/Technology." In Queer Times, Black Futures, New York University Press, 2019): 117-144.

GSU Students Work on Black Visual Intonation

BVI and color in Clockers, Rachel Thigpen

Rachel Thigpen - Artist Statement:

This project explores Black Visual Intonation, a theory coined by Artist and Cinematographer, Arthur Jafa using Spike Lee’s film, Clockers. The challenge within exploring BVI, was in testing a theory whose emphasis is on taking the boundless freedom of sound and exploring it through the editing of images; on a narrative film whose traditions are in its structure. This explains the choice in using a video essay vs. text. It was with this understanding that my goal was to show how the cinematography choices in Clockers, expresses a sense of freedom, through lighting and color by walking the audience through different shots and breaking down a scene.

Rachel Thigpen is a Multi-Disciplinary Artist in the areas of filmmaking, visual art, and design, based in Birmingham, AL. She edits independent films in and manages an art brand, Strawberry Ducks.

Ariel Brown - Artist Statement:

history | alchemy | evolution is a collection of Black works of art and Black life, still and in movement. It features images from artists known and unknown, expanding over two centuries. The piece is accompanied by an improv performance by esperanza spalding, carrying the work in its flow through Blackness.

history | alchemy | evolution, Ariel Brown

Ariel Brown is a writer and visual storyteller with a background in documentary, short, and experimental film. Her writing centers Black stories and characters that explore the gray areas of life, elevating voices that are far too often left out or shut down. Many of her stories point to the metaphysical realms prevalent in the Southern U.S. and worlds that do not yet exist. In May 2021, she graduated from Georgia State University. Now with her Bachelor of Arts in Film and Media, she works as a freelance editor and is a freelance Associate Producer for The Weather Channel.

Arthur Jafa’s Archival Impulse

Right after Jafa visited GSU in April 2016, when he was still finalizing Love is the Message, the Message is Death, he showed his famous “Notebooks” (1990–2007) at the 2016 edition of Made in LA: a, the, though, only curated by Aram Moshayedi and Hamza Walker. These are nearly 200 ring-binders featuring a vast array of images about black expressive culture. The juxtaposition of these images, according to the Hammer website, offer an example of Soviet montage as well as “forms of visual hypothesis on the construction of subjectivity and what Jafa has theorized elsewhere as a decidedly black aesthetic.” The Notebooks were later acquired by MOMA, in New York.

We mention the Notebooks here in order to make a connection with Ben Caldwell’s Project One film Medea (1973), made while studying at UCLA, and this film’s own archival sensibility, which continues with Caldwell’s later film I & I: An African Allegory (1979), which Jafa has cited as a direct influence in his work. The texture and pulsating movement of the clouds of Medea’s opening sequence sets the stage for a seamless transition to a foregrounding of the round shape of a pregnant body, while a woman’s voice delivers a quasi-hypnotic chant punctuated by a recurring refrain: “to raise the race…. to raise the race.”[1] The chant is overlaid on a montage of still images that encompass African peoples and black American figures –stills from ethnographic photography, news photography, popular culture and Caldwell’s own work—recapitulating the breath of the diaspora in the ontogenesis of every soon-to-be born black child in America. The montage moves rapidly, increasingly assuming the pace of the mother’s heartbeat, her breathing, and her chanting all at once. Bathed in a warm hue, the still images display an extraordinary visual consistency, possibly in keeping with Caldwell’s interest in texture and in the relationship between the black body and its environment.[2] This living, breathing, and organic counter-archive abides not by the representational logic that rarely served black bodies on film, but is instead propelled by bodily rhythms and breath. This “impossible” archive is finally congealed in the delicate yet poignant image that concludes the film: a small child interacting with the spherical shape of a white balloon.[3]

It is hard not to think about Caldwell’s archival impulse, and his commitment to moving and sounding archives, as not being influential in Jafa’s and Malik Sayeed’s own process for assembling APEX. See Arthur Jafa’s Theories of Black Filmmaking section for more on APEX

Watch: Medea (Ben Caldwell, 1973)

[1] The chant comes from Amiri Baraka’s poem, “Part of the Doctrine.” See Allyson Nadia Field, “Rebellious Unlearning: UCLA Project One Films (1967-1978), in this volume.

[2] I am referring to the “Awakening” photographic series that Caldwell used for his application at UCLA. Some of the photographs were hand painted and a good number were pictures of “black women in the desert because I thought there was an interesting similarity between our skin, the brownness and the bushes, like our hair, and how it shows itself.” Ben Caldwell, oral history interview by Allyson Field and Jacqueline Stewart, June 14, 2010, unpublished L.A. Rebellion Oral History Project, UCLA Film & Television Archive, in this volume.

[3] Excerpt from Alessandra Raengo, “Encountering the Rebellion: liquid blackness reflects on the expansive possibilities of the L.A. Rebellion films,” in L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, ed. Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, Jacqueline Stewart (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

Kahlil Joseph’s Belhaven Meridian

Belhaven Meridian, Kahlil Joseph, 2010

From: Alessandra Raengo, “Suspension, Revisited,” In Media Res: A Media Commons Project, October 13, 2016

Belhaven Meridian (2010) is the first video Kahlil Joseph directed for Shabazz Palaces. Shot in Watts, on 35mm black and white footage, it is an homage to Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977). It begins with the roar of a car engine over a black screen, then a side shot of a car. A young man is at the wheel and a young woman is sitting on top of the trunk. There is no diegetic dialog but a caption, instead, appears (as it will do, again in Music is My Mistress, 2017, as we discuss in the section “Music-driven Short-form Filmmaking”):

HIM: IT’S TIME.

Then another,

HER: WHERE ARE WE GOING?

She gets into the car—the car that Killer of Sheep’s protagonist Stan could never get to work—and they quickly ride away. The camera follows the car until it disappears behind a row of houses. With a tilt to the left, now the camera stares at an empty street as an attractive young woman enters the frame from the right strolling confidently in the middle of the street. Quickly, and predictably, a young man approaches her and tries to make small talk. They are young and brash and at home. Their steps, whether she likes it or not, quickly assume the same pace, as the (chance) couple’s bodies swing left to right, as they walk.

As if by chance, tilting to the right, the camera picks up the shooting of a (re-enacted) scene from Killer of Sheep itself, which, originally, takes place on the front steps of Stan’s house as two of his “buddies” attempt to lure him to a more facile life of crime as a way out of his predicament: the perverse cycle that entraps him as both the killer and the sheep he routinely slaughters in his day job. This precious glance into the re-enacted “making” of Killer of Sheep—itself a labor of love and respect, and patience, and community—is enough to prompt the camera to rotate on its axis and turn upside down. In this new world, where the bottom is the top and the top is the bottom, the silhouette of a young man appears walking confidently down the same street. Juxtaposed to it there is also an African mask seemingly floating as if lulled by ripples in the very surface of the image. But not for long: the young man inexplicably grabs the mask and rushes through a group of boys who are trying to tackle him, like a running back going for a touchdown. The camera remains upside down and the long take continues as we see him eventually passing the mask to a bike rider from a group of motorcyclists who suddenly ride through the same street. The music settles on a quieter register and the camera follows them gliding through streets progressively filling up with traffic, moving freely and almost floating effortlessly away.

The answer to her question finally comes here:

HIM: WHEREVER WE WANT.

This is one of Joseph’s earliest films, but his archival sensibility is already central to it.

We originally approached it in terms of “suspension” which was the theme of the liquid blackness research project on Joseph which brought him to visit Georgia State University in the fall of 2016. Yet, we re-visit it now because of the way it displays an archival sensibility, which is shared by all the filmmakers discussed in “Music Video as Black Art” pathway.

La Noire de, Ousmane Sembène, 1966

Killer of Sheep, Charles Burnett, 1977

Belhaven Meridian, Kahlil Joseph, 2010

Joseph’s archival move in Belhaven Meridian lifts references from the filmmaking past to engender a new relationship between music and image in the present. Through these references, the film seamlessly travels from 1977 to 2010 Watts, while gathering signs of a (cinematic) Afrocentric past. The mask that the upside down lone silhouetted runner grabs from the “surface” of the image as he is moving through an incoming group of motorcycle riders might belong to the cinematic lineage of the mask that Diouana—the protagonist of Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de—gifts to the French family that effectively abducts her. This mask might then reappears in the streets of Watts over the face of Burnett’s own niece in Killer of Sheep, reinterpreted as a child’s but still connected to its source. Both appearances gesture toward their cinematic origin and index the child’s eye-view that Burnett so extraordinarily adopts to look at his world in 1977, when he is making his film.[1]

Belhaven Meridian also features what the liquid blackness research group described as an “aesthetics of suspension,” quite literally, as a sense of weightlessness in the upside-down-world Joseph creates by flipping the camera, which affords new possibilities of movement to the bodies that move within it. Yet, as Lauren Cramer reminds us, in her reading for Until the Quite Comes, “Icons of Catastrophe: Diagramming Blackness in Until the Quiet Comes,” “lightness” is an effect of architectural structures that disperse mass across multiple grounding positions. Here in Belhaven Meridian too, “suspension” does not usher in an ungrounding—it is not attempting a severance form home, experience, intimacy or truth—but rather engenders an unmooring from the architectures of anti-blackness. Ultimately, in Joseph’s films, lightness is never divorced from gravitas.

Sources:

Lauren Cramer, “Holding Blackness in Suspension: A Study,” In Media Res week on “liquid blackness presents: “Holding Blackness in Suspension: The Films of Kahlil Joseph,” October 10, 2016

Charles “Chip” Linscott, “Distinction and Conjunction in the Films of Kahlil Joseph,” In Media Res week on “liquid blackness presents: “Holding Blackness in Suspension: The Films of Kahlil Joseph,” October 11, 2016

James Tobias, “Untitled,” In Media Res week on “liquid blackness presents: “Holding Blackness in Suspension: The Films of Kahlil Joseph,” October 13, 2016

Sara Cervenak, “byway,” In Media Res week on “liquid blackness presents: “Holding Blackness in Suspension: The Films of Kahlil Joseph,” October 12, 2016

Lauren Cramer, “Icons of Catastrophe: Diagramming Blackness in Until the Quiet Comes,” liquid blackness 4, no. 7 (October 2017)

[1] See Dorothy Hendrix, “The Children of the Revolution: Images of Youth in Killer of Sheep and Brick By Brick,” liquid blackness 1 no. 1 (November 2013)

Black Intentionality:

Bradford Young and Futural Archives

Rekognize, Bradford Young, 2017. Three-channel video installation.

In Bradford Young: Cinema is the Weapon (Corine Dhondee, 2019), once again, Bradford Young claims his own lineage. He lists the visual artists and filmmakers with whom his work is in conversation: Haile Gerima, Larry Clark, Charles Burnett, Andre Dosunmu, Ava DuVernay, John Akomfrah, Chris Ophili, and more. He describes them as his echo-chambers: part of an ongoing conversation in which they are all “checking-in” with one another. Claiming his lineage has been vital to Young’s own framing of his aesthetic research, an act of gratitude towards those who have preceded him and the ground for a concrete plan for the future: what happens when we think about the camera lens that one as the equivalent of Touissant L’Ouverture sward, he asks?

From, Alessandra Raengo, ““Bradford Young’s Futural Archives: Practicing Black Intentionality.” College Art Association, February 10-13, 2021

In his talks, Bradford Young has advanced his idea of “black intentionality” which performs a specific collapsing of the distinction between practice and praxis: black intentionality is both Young’s object of study and the inspiration for his own practice; it is both archival and futural; it is an orientation and a set of values; ultimately, it engenders a specific aesthetic rendering of black space and time.

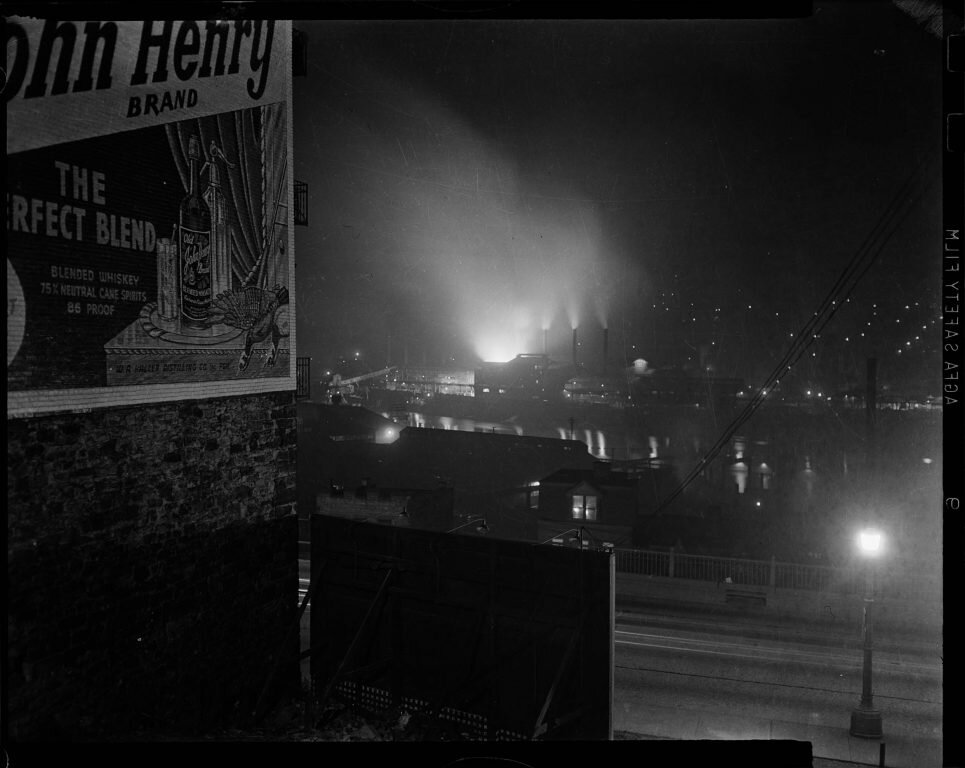

Here we are going to consider the 2017 three-screen installation commissioned by the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, titled Rekognize. As an object of study, Young approaches black intentionality as an archival project. Rekognize is a study in light and black space through an engagement with African American photographer Teenie Harris.

[consider that Black America Again, discussed in the “In Conversation with Art History” section of this pathway is a study on black time and sound, and engages with African American photographer Roy DeCarava. ]

More specifically, Rekognize is a creative engagement with an archive of unattended black practice in the attempt to understand the technique and craft of a master of the past. Craft has to be understood here similarly to the way experimental filmmaker Kevin Jerome Everson does: the way in which one “practices as a way to become good at something.”[1] As Young has often said: “my skill set has come through hard work.” Teenie “One Shot” Harris – “One Shot,” because he supposedly only took one shot of anything—was an exceptionally hard worker: he was seemingly everywhere in the Hill District in Pittsburgh from the late 30s to the 70s: weddings, funerals, baptisms, parties, political meetings, and scenes of anti-black violence.... Young says that In the community he was considered simultaneously a hobbist, a news photographer, a crazy man, and a genius.[2] Regardless of the outcome, Nicole Fleetwood has shown, he never destroyed his work and thus has left behind 80,000 negatives.[3] For ReKognize Young devises a way to engage this archive both in its impressive mass and its minute specificity. He searched it using keywords such as jazz, death, and night in order to unpack Harris’s technique--and, specifically, to understand in what conditions hard work might become a visual style--and in the process show what kind of archival hard work is needed to bring it to the surface. He eventually selected 11 images from a variety of aspects of black life in Pittsburg’s Hill District. Then, he processed them through software that decoded Harris’s use of light, dark tones, and figure placements from which metadata were retrieved. The wedding photo feature above, for example, created 240 text pages of metadata; it showed what Young calls “black intentionality” just underneath the image’s surface.

Through “big data” processing, Young was ultimately looking at ways to engage with the threshold where black intentionality might become a recognizable style.

Rekognize, Bradford Young, 2017. Three-channel video installation.

The installation’s center channel flashes the original photographs and waterfalls of metadata. The two outside channels feature Young’s contemporary footage of locations in the Hill District which is where Harris operated. The metadata, Young says, shows the relationship to the shadow of a thriving black middle class. When the Steel Mills were in full swing, they produced particles in the air that allowed Harris to catch light in a particular way. Instead, the contemporary light study Young performed in the same areas, with particular attention to Pittsburgh’s tunnels as charged black spaces connected to the Great Migration, document the end of the black middle class. Working only with “what’s left behind” in the atmospheric light leads to an unavoidably different outcome. Even then, Young’s images flaunt their processual nature: the slowly come into and out of focus, they are animated by flares, or they show the same location with two slightly different focal setups. Opticality, in other words, is archival and Young deploys it to bend time and connect the then and now, as well as to ponder on what might it take for a consistent practice to emerge as a conscious style.

Jazz pianist and composerJason Moran used the “waterfall of numbers” to write the score for the installation to create a specifically black sonic space to match the way the light already did in Harris’s photographs. As Antwaun Sargent explains, he used almost exclusively the bottom 10 keys of the piano and mapped them onto the binary code produced by the metadata. Here black intentionality comes again from within, while it also manifests in the conversation with jazz as “pure speculation” as when Moran “imagines abstractly the sound of the flashbulb from Harris’s camera or the gunshot that killed Raymond Jones in Crestas Terrace back in 1949.” He then added trap beats and the 808 machine to further indicate Blacks’ relationship to base culture.

In Black America Again, as already discussed, Young is in dialog with DeCarava’s practice of letting a photographic image go black as a consequence of attending to its sound. He describes DeCarava’s work as an exercise in patience and restraint, a laying in wait to “shroud the moment” —which is often a musical moment—and compares it to the note that, famously, John Coltrane heard in his head but could never play on the horn. What does that look like? Young asks. How does that torment a man’s soul?” In Black America Again, opticality is deployed to bend relationships to space in order to investigate the double valence of black time expressed through the “again” of the film’s and the album’s title.

Fred Moten has already shown how the philosophical project of phenomenology cannot “intend” the black, because “phenomenology refuses the world to things” (18) and “racism denies the thing its humanity and denies humanity its thingliness.” Then he asks: “What if one bears, while also responding to, the otherness of entities? How does such bearing shape one’s response?” In his futural archival engagements, Young embraces what Moten calls “being sent”: by Teenie Harris, Roy DeCarava, and John Coltrane; by their ensembles and the ensemble of their ensembles. Like Coltrane’s note, black intentionality is “poetry from the future,” as Kara Keeling describes it, with Marx’s turn of phrase, a type of “wealth held in escrow,” and an analytic of the ensemble across time and space. In this, it signals not only the pursuit of a black aesthetic practice but also art-making that is also blackness-making.

[1] Alessandra Raengo and Lauren McLeod Cramer, “’There is No Form in the Middle: Kevin Jerome Everson’s Massive Abstractions,” liquid blackness: journal of aesthetics and black studies 5.2 (forthcoming, Fall 2021)

[2] Bradford Young, “Bradford Young and the Visual Art of Black Care.” Artist Talk at Georgia State University, April 15, 2018. https://vimeo.com/291961328

[3] Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling vision: Performance, Visuality, Blackness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Motion Practice

Black Magic, Cinque Northern, ft. Storyboard P, 2014

Arthur Jafa described “filmdancer” [1] Storyboard as successfully embodying the filmmaker’s theory of “Black Visual Intonation” into actual movement. He noted Storyboard’s ability to produce “special effects” in his performance through the manipulation of speed, as if the dancer’s movements were capable of performing the uncanny effect of slow motion by altering the frame rate.[2]

The liquid blackness research group studied Storyboard P’s work in 2018 in the context of a research project titled, “Figuring Suspension: A Study of Visual Recording Artist Storyboard P,” also featured on this website. This research project focused on movement, affect, synchronization, black performance, and animation. It mobilized a series of theoretical and methodological frames that might help understand the uniqueness of Storyboard’s performance style and the new possibilities that it opens for (or the new attitudes that it demands from) the location and gaze of the camera, the pace and phrasing of editing, and the possibility for the apparatus to abide by the gestural integrity of the performer rather than harness it to lubricate its own cumbersome functioning.[3] Storyboard P, in other words, appears to place established formal and aesthetic protocols “in suspension,”[4] contributing to a reflection on movement that bridges, by blurring, the distinction between the performing body and the performing image (Maurice) at multiple scales. That is, perhaps Storyboard’s dancing style can be regarded as a more liberated switch point between sound and image, as a self-directed movement, so that his extraordinary craft might offer a place to begin to think anew not only the way traditional sound and image relations have historically straightjacketed the black body in mainstream cinema but also the countless expressive possibilities that become available once synchronization is tossed aside, conventional speed is upended, and black gestural possibilities are kept intact, in all their unruly capabilities.

[1] Erin Brannigan, Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

[2] MIT APEX_TNEG, February 25, 2013

[3] Alice Maurice, Cinema and Its Shadow: Race and Technology in Early Cinema (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2013)

[4] For the idea of aesthetics of suspension see liquid blackness 4, no. 7 “Holding Blackness: Aesthetics of Suspension” as well as the research project, Holding Blackness in Suspension: The Films of Kahlil Joseph.

Black Magic, Cinque Northern, ft. Storyboard P, 2014

Figuring Suspension: A Study of Visual Recording Artist Storyboard P: liquid blackness in conversation with Thomas DeFrantz

Watch: Everything is Dance (ft. Storyboard P)

Jenn Nkiru’s Cosmic Archeology II

Jenn Nkiru learned the importance of focusing on process partly from her mentor, Haile Gerima and understands the finished work simply as the reportage of the process that engendered it. A part of Nkiru’s process is the sociality of blackness through individual people who come together and “play” as a whole ensemble—she calls the entire crew, the “filmmakers --which, in turn resonates with Nkiru’s archival method, modeled after her DJing practice. In her GSU talk, “Jenn Nkiru’s Pan-African Imagination: Black Studies as Aesthetic Practice,” she said, “I often say if I were digging for records, I would go to record shops for hours and sift through different records and play records and then listen for the break… And think this is what I want to use.” She continues, “[It’s] the same way with the archive. I’m looking at the archive. Sometimes looking at pieces that are four, five, six hours in length and taking out maybe […] two seconds, so it’s a practice on that […] level.” Nkiru looks at the archive as “a million-piece puzzle.” She explained, “I'm trying to use these puzzle pieces [almost to awaken]. The idea […] is that there's a lot of information and a lot of knowledge that is lying latent… [and] we don't have the stimuli to bring those things up….”

Through Nkiru’s digging in the archives, she creates cinema that is sampled, remixed, and dubbed for a new audience. In a Financial Times article by Harriet Fitch Little, titled “Film-Maker Jenn Nkiru’s Brain-Bending Vision,” her work is described as “superfluid.” Nkiru explains, “‘I’m trying to bridge the academy, pop culture and art.’”[1]

Watch below two short clips from“Jenn Nkiru’s Pan-African Imagination: Black Studies as Aesthetic Practice,” Artist Talk. Georgia State University, April 2019, in which the artist discusses her relationship to the archive and how she understands “queer visibility” in relation to it.

[1] We are grateful to Jazmine Hudson for curating this segment

The Unruly Archives of Hip Hop Music Videos

This section is dedicated to two case studies that help conceptualizing the way in which contemporary music video address their own archival concerns. The first, Apollo Brown’s Thirty Eight (2014) is the centerpiece of Lauren McLeod Cramer’s essay “Building the Black (Universal) Archive and the Architecture of Black Cinema,” In her abstract she describes her project as follows:

Thirty Eight, Apollo Brown, 2014

“Black cinema, as an institution and medium for recording and preserving Blackness, is a vast and complicated film category. A true Black cinematic archive would mean imagining an archive of everything, and everything in between. The work of Black cinema studies is to make sense of this archive and articulate the theoretical productivity of the category. This essay explores the appearance and shapes of these structures of knowledge, how they are constructed around Blackness in the hopes of containing and making sense of its extremes, and argues that exploring the vast field of Black cinema and Black cinema studies is an architectural endeavor. Using Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel” as a model, this article performs a spatial analysis of a short film to understand how the Black cinematic archive coheres disparate bodies, objects, and images into a unified and coherent structure.”

This is America (Childish Gambino, 2018)

The second is Donald Glover’s This is America (Hiro Murai, 2018), which Michele Prettyman discusses in her essay “The Persistence of Wild Style: Hip-Hop and Music Video Culture at the Intersection of Performance and Provocation." In her essay, Prettyman first discusses This is America within the context of the groundbreaking video for the South Bronx’s Grand Master Flash and the Furious Five’s (GMFFF) iconic song “The Message” (Alvin Hartley, 1982), and the way SoundCloud music streaming enabled the rise of new iterations of hip-hop music and video form, briefly discussing a video from the late provocateur XXXTentacion entitled “Look at Me” (James “JMP” Pereira, 2017). Her focus is to show what she describes as the “persistence of wild style” and its attendant processes of initiation. She writes: “Embedded in the wild style trope is the notion of coding and decoding phrases, references and visual cyphers that may be disorienting, inaccessible, or so purposefully cryptic that those who are uninitiated may not be able to gain access to the world of meaning created by its makers.” (152) By attending to the reappearance of the “bent knee” pervasive in the minstrel theater tradition, Prettyman reads This is America as a work that “engages the archive of racialized movement and dance from the nineteenth century [and] is part of a larger narrative that both illuminates and obfuscates the perils of Black life and performance by foregrounding the slippage between visibility, success, and vilification.” (152, 155)

Sources:

Lauren McLeod Cramer, “Building the Black (Universal) Archive and the Architecture of Black Cinema,” Black Camera: An International Film Journal 8, no. 1 (Fall 2016): 131-145

Michele Prettyman “The Persistence of Wild Style: Hip-Hop and Music Video Culture at the Intersection of Performance and Provocation," JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 59, no. 2 (2020): 151-157.

Thomas DeFrantz, “This is America,” b.O.s. 7.3, edited by Lisa Uddin and Michael Boyce Gillespie, August 27, 2018

More sources, available in the liquid blackness research page devoted to Donald Glover