Aesthetics Appropriate to Conditions: A Collaboration between Digital Cinematography and Theories of Black Filmmaking

Screengrab from Kye Brewer’s Medea (2020)

OVERVIEW

In the Spring of 2020 Professor Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz and Dr. Alessandra Raengo launched an unprecedented collaboration to pair film theory with practice by bridging together two already existing classes—Digital Cinematography and the Senior Seminar: Theories of Black Filmmaking— so that Students would learn the profound interrelation between theory and practice and would understand that one is the expression of the other. The goal was to offer to them the opportunity to develop “heritage knowledge” (King and Swartz, 2018), i.e. the possibility to adopt an episteme centered on the history of their own (expressive) culture, as represented in the microcosm of the liquid blackness archive.

The guiding idea for this groundbreaking collaboration was “aesthetics appropriate to conditions,” which is the way a seminal essay by film studies scholar Paula Massood had described Charles Burnett’s film Killer of Sheep (1977), a foundational film from the output of the LA Rebellion filmmakers.

Aesthetics appropriate to conditions” was used as a common thread in both classes as an immanent device to allow the students to first detect and then develop their own “heritage knowledge” and begin to write themselves into already existing archives.

This work of “writing themselves into the archive” was structured into the production students’ first major project: Project One.

PROJECT ONE: LA REBELLION

Project One asked our students to re-create and/or adapt an original LA Rebellion Project One film in ways that would reflect students’ own, contemporary conditions, which could include but not be limited to:

● Conditions of production (which includes Atlanta itself, which many students encounter as a contested space due to histories of racial struggle and gentrification)

● Identification/political alliances/sensibilities

● Geopolitical conditions

● Artistic competencies, and more, i.e. the art historical or media-making tradition the constitutes their default language

● Relationship between politics/ethics/aesthetics

Students were given the option of adapting an entire Project One film or an excerpt. To prepare for this work, they watched several films from the LA Rebellion canon, and engaged in in-depth, analytical conversations with Dr. Raengo and the theory students, in which they analyzed the films’ symbologies, structure, and experiments.

We felt that engaging our students with the Project One archive would offer them an unique opportunity to apply these critical discussions--to think deeply and capaciously about the political relevance of aesthetic choices; forge their relationship to cinema by way of decolonizing aesthetic experiments; consider aesthetic choices as expression of their conditions; and promote students’ creative agency to respond productively to the contemporary moment. How might cinema, we wondered, both as an aesthetic and industrial formation, be a space for students to not only take leadership as cultural producers, but also to engage in dialogue with creative movements such as to inform their own theorizing of their experiences of Blackness, Queerness, Immigrant-ness, Alterity, and/or sociopolitical identit(ies) more broadly?

This Project One exercise fulfilled another important goal of our collaboration shares with the liquid blackness project, which is the focus on the generative work of the archives of the black visual and sonic arts . In introducing students to a filmmaking language that is completely unmoored from Hollywood’s, that is in fact seeped into the black arts, we not only compel student engagement, but we create conditions for students to meaningfully contribute to the archive, by seeing themselves in it and writing themselves into it. In this iterative relationship, we enact and reproduce across cohorts (and generations), the dynamics of the ensemble and the politics of sociality. (Raengo, 2020).

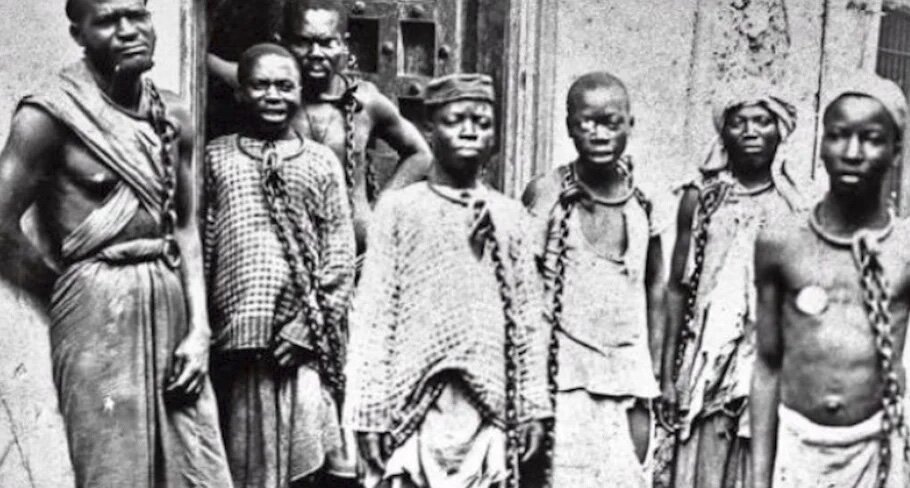

It’s important to note here that, this act of re-creation is not an attempt to erase important and singular contexts of the original Project One films, which student Maggie Fleming describes as “Black community shaping their own self-image and rewriting the definitions and false representations imposed by white society.” Instead, this work 40+ years later, is an affirmation of methodology responsive to the lived, cultural experiences of its producers (Massood, 23) as well as a way to expose and/or resist “film’s devastating capacity to colonize” (Gerima, 2010, 27).

Our students’ Project One films do in fact continue in the work of a decolonizing film practice, one that contributes to what Firelight Media calls the “liberatory canon.” Some of these short films map the aesthetic leadership of the LA Rebellion filmmakers onto Kashmiri independence struggles; the work of fostering Queer care communities; and challenging labor injustice specifically as affects Latinx/Latin American communities.

Project One Films

OUR OWN HISTORY AND CONDITIONS

Three important factors/histories converged to make this multi-stakeholder collaboration possible:

In the Fall of 2017 Dr. Raengo began teaching a graduate seminar called Theories of Black Filmmaking in order to focus on the way filmmaking practices from the black diaspora that had been part of the liquid blackness group’s research projects and archive had directly responded to industrial, social, and ideological constraints as well as also severe limitations of their contemporary film theory, which never adequately addressed the ways in which the cinematic apparatus--and so much of film theory--had assimilated blackness to serve its own purposes. The main goal of the class was to “glean” a black film theory through a close textual and contextual analysis of black filmmaking practices and, consequently, also challenge the divide between what constitutes theory (who can produce it and where it might be found) and what constitutes practice. Ultimately, the seminar sought to offer students ways to witness a new cinematic language in the making and through making.

In the Spring of 2019, Professor Ebrahimi Bazaz joined Georgia State University as Assistant Professor. She came to GSU with an extensive background in community-engaged, reflexive documentary practices intended to decolonize both social relations and documentary practices themselves. This work proceeds from Freirean models of praxis and what activist writer Harsah Walia describes as prefiguring. In the work of decolonization, Walia (2013) writes, “prefiguration is the notion that the methods we practice, institutions we create, and relationships we facilitate within our movements and communities align with our ideals.” Prefiguring within creative process is the notion that a project’s methodology, creation processes, formal and aesthetic choices and even exhibition strategies all aligned around a value system.

In Prof. Ebrahimi Bazaz’s project 360-degree documentary, “How to Tell a True Immigrant Story,” a prefigurative strategy generated processes of community dialogue and co-creation over years, resulting in a cinematic form that is choral, circular (shaped in the 360-degree VR sphere), and that resists the ethnographic gaze. The documentary “subject” is re-imagined as an “agent” in the piece, which is a reflection of the film’s commitments to centering in the experiences of people most vulnerable to white liberal social relations. Additionally, the film’s formal structure, narrational strategies, and compositional choices all are designed toward certain values-aligned outcomes of encouraging the white liberal viewer to be critically aware of their own desire and acts of looking. The film’s prefigurative process is discussed in further detail here.

These values, this manner of critical inquiry, and this conviction in the power of media making to participate in social transformation are entirely value-aligned with the work of our collaboration. Prof. Ebrahimi Bazaz’s work at the intersection of theory, practice, and social justice organizing helped to foster a classroom space in which students from a variety of backgrounds could be guided in using theories of Black filmmaking as a lens to frame personally meaningful movements.

Graduate student Donovan Stanley’ is an Atlanta-based filmmaker and writer whose practice is committed to the creative potential of co-creative modes. Donovan had previously taken Theories of Black Filmmaking with Dr. Raengo and Digital Cinematography with Prof. Ly Bolia. He was thus equipped with both the skills and the theoretical foundations required by this unique course pairing. An emerging, talented, and generous filmmaker, Donovan has often expressed how much Theories of Black Filmmaking transformed his understanding of what cinema can be and do, while Digital Cinematography had taught him the skills to execute his expanding cinematic vocabulary. True to his own ethos rooted in resource sharing and community building, Donovan was happy to “pass along” the knowledge he’d acquired and introduce students to the historical lineage and social change potential of Black cinematic aesthetic traditions. Donovan was also very invested in equipping students with the skills they need to make films in configurations outside of the Hollywood studio system: independent, ensemblic, experimental.

PEDAGOGICAL OUTCOMES:

This collaboration has led to learning and professional outcomes for our students and ourselves.

Learning Outcomes:

By integrating learning materials for both classes, and having the students share some of their meeting times, this collaboration asked all students to reflect on:

● The critical thinking embedded in any type of “making,” whether that is the writing of an essay, the shooting and editing of a film, or the creation of an film essay that critically engages with black visual artifacts.

● The language this critical thinking needs to adopt in order for their voices to be heard and to be true to themselves. This was the function performed by the liquid blackness archive as a repository of previous experimentation with productive conversations between filmmaking practices, the black visual arts, and the rich and unruly archives of black music, which have taken place from the 1960s onward.

● Understand and practice first-hand the intimate connection between personal and collective expression and the political work of form.

● Reflect on what might constitute their “conditions” and think about how their aesthetic choices might express that.

In keeping with the mode of production and political choices of Killer of Sheep, we also emphasized the idea of both filmmaking and intellectual production as collaborative practices. In the Theories of Black Filmmaking seminar this was signaled through the idea of the jazz ensemble as the model for what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten (2013) have described as “black study.” Not only have the filmmakers of the liquid blackness archive collaborated with each other in various forms of ensembles, but they also draw inspiration from the improvisatory, egalitarian, free-form sociality of the jazz ensemble in the way they approach their own filmmaking process (Raengo and Cramer, 2020)

Praxis and Outreach Outcomes

Modeling egalitarian and improvisatory collaboration in our pedagogical approach to these two overlapping classes, we sought to offer an example of how the very structure and modes of engagement of a learning environment can also foster important political work.

We enacted this political work through the formation of AMPLIFY: media arts for collective strength, a collective of faculty in the film department Georgia State. Amplify aims to provide an alternative to institutional violence by creating a space constructed in care. We demonstrate this care through a variety of commitments including exhibitions of student works that challenge anti-Blackness; public dialogue concerning the thoughtful deployment of moving images toward exposing and dismantling systemic oppressions; fostering of career pathways for BIPOC, Queer, and variously-abled filmmakers; and supporting local initiatives in Atlanta wherever possible. Responding to our students’ voices and works, AMPLIFY seeks to foster artistic and critical dialog around systemic anti-Blackness as a site for the articulation of liberatory demands.

AMPLIFY's first actions were to host a curated conversation series to showcase emerging radical cinematic aesthetics which advocate, protest, reflect, heal, empower, affirm, uplift and cultivate community. Films produced in our collaborative class have been featured in this conversation series. Conversations are moderated by leading practitioner-scholars in the field, are hosted publicly, recorded, and archived on the liquid blackness website. That is: students’ engagement with the archives contributes meaningfully to the archive.

This conversation series has also opened doors for students into professional opportunities, which we see as another pedagogical outcome of the work of our collaboration.

Sources cited:

“Conversation with Alessandra Raengo,” Journal of Visual Studies, 35, no. 2-3 (2020): 99-104

Ebrahimi Bazaz, A., and Liz Miller. “Invited and Implicated: Toward Critical Reflexivity in Non-fiction VR.” The Digital Radical (June 2020). https://cdcs.asc.upenn.edu/aggie-ebrahimi-bazaz-and-elizabeth-miller/

Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013

Jackson, John T. and Haile Gerima. “Decolonizing The Filmic Mind: An Interview with Haile Gerima.” Callaloo 33, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 25-36.

King, Joyce E., and Ellen E. Swartz. Heritage knowledge in the curriculum: Retrieving an African episteme. Routledge, 2018.

Massood, Paula J. "An aesthetic appropriate to conditions: Killer of Sheep,(neo) realism, and the documentary impulse." Wide Angle 21, no. 4 (1999): 20-41.

Raengo, Alessandra and Lauren McLeod Cramer, “The Unruly Archives of Black Music Video,” in: IN FOCUS Dossier: “Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art,” ed. Alessandra Raengo and Lauren McLeod Cramer, Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 59, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 138-144

Walia, Harsha. Undoing Border Imperialism. AK Press. 2013.